It was all over in fifteen minutes.

When Canadians celebrate Canada Day tomorrow, they’ll be commemorating the birth of a nation, cobbled together in a process known as Confederation, a coming-together of former British colonies to form one, single, and united nation that would grow into what it is today one of the pre-eminent countries of the world. It all started officially on July 1, 1867.

Newfoundland was a British colony as well, but didn’t elect to join the others to become part of the new Dominion of Canada. They didn’t join the rest of us until 1949, becoming a fully functioning province of that dominion.

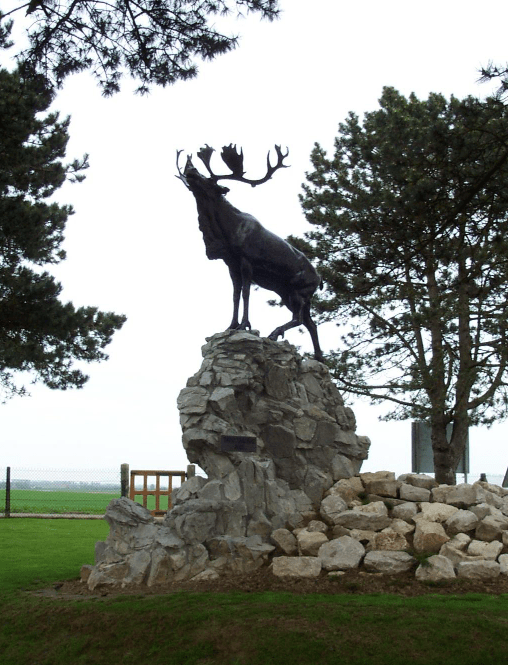

It’s Canada Day in Newfoundland as well on July 1, but it’s not known as that. In fact, the day is known as Memorial Day, and instead of a day of celebration, it’s a day commemorating the greatest tragedy ever to befall the province known as “The Rock.” A tragedy that took place on July 1, 1916, at a place called Beaumont-Hamel.

At 8:45 AM on that day, the Newfoundland Regiment, now known as the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, went “over the top” as part of the bigger Battle of the Somme, a major British-French attack on German defences designed to take the pressure off the French who were being bled white at a place further up the line, in Verdun, perhaps the greatest bloodbath in a war full of bloodbaths.

At battalion strength, the flower of Newfoundland’s youth, at least its male youth, attacked the way everyone attacked in those days, walking across an open battlefield that had been purportedly “softened up” by one of the largest pre-attack artillery barrages in history. In the middle of that lethal space, that space that existed between warring armies, there was a tree. It stood by itself in that barren landscape, all other trees blasted away, leaving a No Man’s Land full of pock-marked depressions made by artillery from both sides.

And this tree.

Battered and damaged, dead if not dying, this tree in the middle of No Man’s Land was to be the rallying point for the regiment, a place to gather mid-attack, and a place from which subsequent attack vectors would be identified for exploitation. Some of the regiment made it to the tree that morning, but few advanced beyond it. It’s become known, if it wasn’t already at that time, as the Danger Tree.

At 8:45 AM, 22 officers and 758 enlisted men went over the top. The Germans were ready, having been in place and entrenched for almost two years. If nothing else, the Germans were among the best at defensive warfare and engineering, so they had dug deep dugouts and tunnel systems to protect themselves from allied artillery. That big artillery barrage, including the British detonation of a massive mine under German positions, only served to alert the Germans to the onslaught of a major attack. When the big guns went quiet, the Germans scrambled up to the surface and manned their Maxim machine guns and harnessed their own artillery. And that place, that rendezvous spot at the Danger Tree? That just happened to be a point where the Germans had pre-determined interlocking fields of fire for their machine guns.

In fifteen minutes, all the officers and 658 enlisted men were casualties. Of the 780 men involved in the attack, only 110 of them survived and only 68 of them were available for roll call the next day.

For a colony of some 240,000 souls at the time, losing close to 1000 men is close to an existential tragedy. To lose them in the time it takes to brew a cup of tea makes the whole thing even more of a sombre day.

Fifteen minutes and 80% casualties. Close to a thousand young men dead, including fathers, brothers, husbands, and boyfriends. Those who had their own families had them no more. And those who didn’t never would. Almost an entire generation of young males lost, just like that.

So it’s different in Newfoundland on Canada Day, although Newfoundlanders have demonstrated and proven to be some of the most loyal Canadians, still continuing to serve in the Canadian Army in significant numbers.

The regiment still exists, now known as the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, a distinction bestowed upon them by King George V at the end of World War I. Today it’s mostly a reserve formation, part of the 37th Canadian Brigade Group, which in turn is part of the 5th Canadian Division. In terms of regimental pride, the story of the Blue Puttees ranks up there with the story of any other infantry regiment, although they are placed dead last in the order of Canadian regimental precedence, something that is determined, at least to a large extent, by seniority.

The story is as heroic as it is tragic. And it’s important for the rest of us, those Canadians not from Newfoundland, to know the story and respect the sacrifice.